I’ve been meaning to write something about Meerkat for a while, but haven’t got around to it. Now that competing product Periscope has launched, I feel like it’s finally time. A brief primer for those to whom these names mean nothing: Meerkat launched several weeks ago, and is a barebones personal video broadcasting app for iOS, and Periscope is a very similar but more polished app which Twitter acquired a while back and launched yesterday.

Watch me talk about this stuff

I did a quick interview with Reuters TV yesterday on the topic of these two apps, and you can see that here.

Also yesterday, by way of testing Periscope, I did a quick Periscope session where I talked about the two, which I subsequently uploaded to YouTube:

Meerkat’s faster start helped rather than hurt Periscope

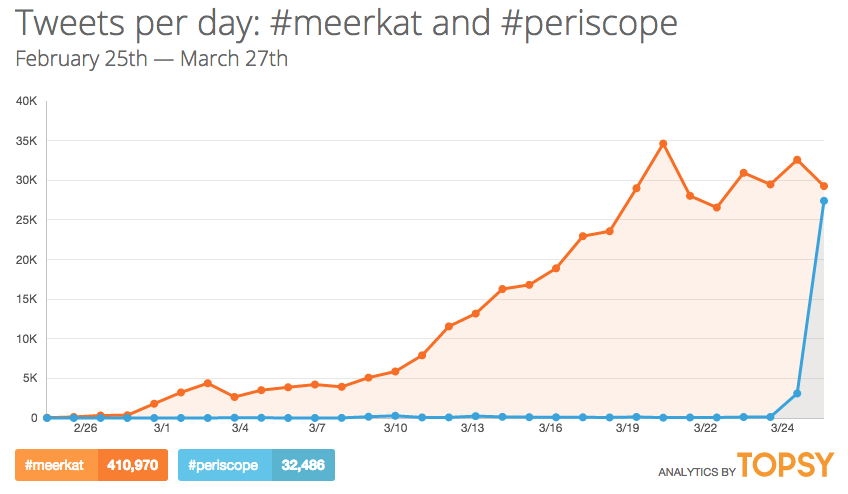

Given that people knew about Periscope even before it launched, there has always been discussion about how the two would compete and whether Meerkat would have such a lead by the time it launched that Periscope would be dead in the water. I was always skeptical about that – being first doesn’t always (not even mostly) lead to winning in these battles. and first-day results from Periscope seemed to bear that out. Dan Frommer of Quartz posted this chart this morning:

This shows the number of Meerkat and Periscope-related tweets over the last few weeks. As you can see, it took Meerkat most of that time to reach the 30k per day mark, but Periscope almost hit that number in its first day. What I’ve wondered about, and what now seems to be happening, is that Meerkat actually did Twitter and Periscope a huge favor by teaching people about the concept and letting them experiment with it, such that by the time Periscope came along people immediately understood the value proposition.

I prefer Periscope so far

On top of that, as I alluded to in my first paragraph and in the video above, I find Periscope to be much more polished and easier to use than Meerkat. Meerkat seems very much like a cheap Android app, somewhat ugly in its interface and hard to navigate around. Periscope seems much more better thought out, nicely designed and professional, much more at home on iOS (the only platform both apps are on, for now). And of course then there’s the fact that Meerkat got cut off from Twitter’s social graph shortly after launch, which will make it harder for Meerkat to sign up new users, because the process of finding followers will be much harder. For power Twitter users, custom curation of following and follower lists has always been important, but for mainstream users easy setup is key, and Meerkat has likely lost some of that.

Periscope isn’t perfect – the fact that I had to post the video of my session from my camera roll to YouTube rather than being able to share it directly from the app is something I hope they’ll fix in time. Both apps force you to use a portrait orientation, which is fine for selfie-style videos but poorly suited to either group shots or shooting a scene (and, as this BBC citizen journalist expert mentioned, poor for incorporating into professional news broadcasts too). But I like the fact that it keeps sessions in the app for viewing after they’ve ended, unlike Meerkat, although finding those needs to get easier.

It’s still early days here, but I think Periscope has a fantastic chance to dominate, given its polish, its ownership, and the fact that Meerkat laid the groundwork for it. Meerkat isn’t necessarily doomed, but there’s little in my mind to recommend it over Periscope, and I think the latter will pretty quickly become dominant.

Why did these products break through now?

The other question worth thinking about is why these two apps suddenly appeared at this time, and what’s made them so successful when other previous efforts have failed. I think it comes down to two main things, and a third factor which has helped too:

- Mobile-first products – these products don’t really exist in any meaningful sense on the web or desktop – they’re mobile-first, and only enable streaming from iPhones. Meerkat allows sessions to be viewed from the web, while Periscope doesn’t, but they’re clearly designed for both broadcasting and viewing on the device you have with you all the time. This also allows them to tap into notifications, which are huge for real-time services.

- Twitter as megaphone – speaking of real-time, Twitter has become the real-time platform, with many people keeping it open and watching the tweets roll in more or less as they happen. It’s already been the real-time platform for covering current events, but that has largely meant text and the occasional picture. Video adds a whole new dimension to this real-time element, and Twitter becomes the megaphone through which these broadcasts from apps get shared with the world. Tapping into existing Twitter audiences and leveraging the retweet as a way to seamlessly rebroadcast popular streams is a huge part of why these services are successful. It’s also the biggest reason Twitter’s acquisition of Periscope makes sense – it adds another vital dimension to Twitter’s “media” strategy.

- Tech reporters getting on board – this was arguably less a catalyst than an accelerant, but quite a few tech reporters quickly jumped on board with Meerkat, tried it out, broadcast themselves and got the product through its awkward “here’s me eating my lunch” phase that all sharing platforms seem to have to go through. Though that phase was repeated as Periscope launched as regular people tried it out, that early reporter experimentation meant we quickly learned what worked and what didn’t, and this early experimentation by those with significant followings helped the product to get far more attention than it would have got through more of a grassroots adoption by regular people.

Breaking into the mainstream is the next challenge

The challenge will be transitioning from this early success among those who have significant followings on Twitter to regular people. Are ordinary people whose Twitter audiences consist mostly of people they know in real life going to use either of these two services? Or will their broadcasts only be meaningful when they happen to find themselves in the right place at the right time, as with yesterday’s building collapse and fire in Manhattan? I suspect that over time we’ll see some new Meerkat and Periscope celebrities emerge, just as we’ve seen Instagram and Vine give rise to new personalities with significant followings seemingly out of nowhere. But I think that, most of the users will be viewing, not streaming, and that actually fits great with Twitter’s new direction.